Utah State Wide Needs Assessment: Domestic Violence, Sexual Violence and Human Trafficking - 2022 White Paper

Fukushima, A.I. (2022). Utah Statewide Needs Assessment: Domestic Violence, Sexual Violence and Human Trafficking - 2022 Report. Salt Lake City, UT: Gender-Based Violence Consortium, University of Utah. https://gbvc.utah.edu/utah-state-wide-needs-assessment-2022/

Download the 2022 Report

UNA Final Report 2022 High Resolution

UNA Final Report 2022 Low Resolution

Also available at the Utah Women's Health Review.

Report Contents

Key Terms

Introduction

Methods

- Participants

Community Perceptions

Marginalized Communities

- American Indian / Alaskan Native

- Communities of Color

- Immigrant Communities

Marginalized Communities cont.

- LGBTQIA+

- Disability

Services & Response

- Change

- Barriers

Needs

- Crisis-line

- Housing

Needs cont.

- Transportation

- Medical

- Justice & Law

- Campus Response

- Violence Prevention

Recommendations

Bibliography

Key Terms

- Scholar Sarah Deer illuminates how the Colonial legal system has failed Native communities due to patriarchy and oppressive structures that condone violence, perpetuating the oppression of marginalized communities.

- Domestic violence is the willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another. It includes physical violence, sexual violence, psychological violence, and emotional abuse. The frequency and severity of domestic violence can vary dramatically; however, the one constant component of domestic violence is one partner’s consistent efforts to maintain power and control over the other (NCADV n.d.)

- Severe forms of human trafficking are: Sex Trafficking - The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act which is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age; or Labor Trafficking: The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud or coercion, for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage or slavery (USA 2020).

- Indigenous people are Native people's to a land. Indigenous may also include other Native peoples from other contexts who have settled on other lands.

- LGBTQIA+ is a term to refer to people who are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, Asexual, Queer and other sexually and gender diverse communities.

- Native American / Alaskan Native comprises of the indigenous peoples of the North American continent, commonly referred to as the United States, and also in other contexts as Turtle Island.

- People of Color is a complex term to refer to racial and ethnic minoritized communities such as Asian American, Black, African American, Hispanic, Latino/a/x, Pacific Islander, and Mixed Race or multi-racial people.

- Sexual violence is an all-encompassing, non-legal term that refers to crimes like sexual assault, rape, and sexual abuse (RAINN 2022).

Introduction

The purpose of the Utah State Wide Needs Assessment is to understand the extent to which resources are available to address domestic violence/intimate partner violence, human trafficking, and sexual violence in Utah:

- Services available to assist survivors and victims of domestic violence/intimate partner violence, human trafficking, and sexual assault in Utah, particularly in underserved communities (including outreach, direct services, housing, prevention, and culturally relevant services).

- Estimation of the types and extent of survivor needs, including in underserved communities.

- Assess for the presence and extent of gaps pertaining to geographic location (rural and urban), service type, and accessibility, including underserved communities.

The study addresses the needs of survivors of domestic violence (DV), sexual violence (SV), and human trafficking (HT) in Utah. The study takes place in Utah which has a population of 3.3 million people, and is growing rapidly in size and diversity. 14.4% of the state are Hispanic/Latino, 2.7% are Asian, 2.6% are two or more races, 1.6% are American Indian/Alaskan Native, 1.5% are Black/African American, and 1.1% are Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

There is a need to respond to violence in the state of Utah. The overall perception of domestic violence, sexual violence and human trafficking in Utah are that conditions have worsened, the physical violence has become even more deadly. While participants of this study described a growth in local response, they illuminated how silence and the culture of Utah continues to create challenges for survivors.

Data from the Utah Department of Health has shown that one in four adult homicides are domestic violence-related, and that 1 in 10 males or 2 in 11 females will experience interpersonal violence. In 2018, a report from the Utah Department of Health showed that intimate partner violence (IPV) affected 18.1% of adult females and 10% of adult men (Utah Department of Health 2018). And 37% of transgender people will experience domestic violence in their lifetime (Peitzmeier et al., 2020). The same report indicated that less than 15% of Utahns who experienced IPV sought help for it. And between 2018 and 2019, there were 72 cases of strangulation identified related to domestic violence in Salt Lake City alone (Fukushima et al., 2020). Homicide is more likely for victims who experience strangulation by 750%.

Across the state of Utah, domestic violence organizations conduct a Lethality Assessment Program (LAP). Between 2016 and June 2021, 24,202 LAP screenings were conducted. It was found during the last two years of LAP screenings that 3,653 cases faced high danger (Utah Domestic Violence Coalition 2022).

Similar data shows that rape is the only violent crime in Utah with a rate higher than the national average. Research conducted by Dr. Melton illuminates that 40% of CODIS (Combined DNA Index System) hits are serial offenders. RAINN conveys that 1 in 6 women experiences sexual violence in her lifetime (n.d.).

Human trafficking is under-reported and more difficult to identify. In 2020, there were also 182 victims of human trafficking identified in the state from the National Human Trafficking Hotline (n.d.) and 1,413 cases 2017 to 2020.

Although victims of domestic violence, sexual violence, and human trafficking experience these forms of abuse specifically, they oftentimes may intersect in the form of polyvictimization where a survivor may experience multiple forms of abuse in their lifetime.

This report reflects the tip of the iceberg. There is limited data on domestic violence, sexual violence and human trafficking in Utah and how minoritized populations are impacted by violence. Additionally, there is a lack of comprehensive studies on American Indian and Alaskan Native communities, and much of the data represents national studies. Therefore, this study represents what Sonia Salari refers to as the iceberg effect of maltreatment, where what is known is the tip of the iceberg and there is so much unknown, and many survivors who experience violence that goes under-reported.

Methods

Previous statewide needs assessments focused on domestic violence service providers and human trafficking noted similar areas necessary to improving response within Utah. Gezinski (2017) recommended specific steps to be taken within each section (funding, education, legal services, community, continued research), including outcome measurement and conducting a statewide assessment every 3-5 years. Fukushima et. al. (2018) recommended long-term comprehensive service provisions, coordinated community response, increased outreach to identify vulnerable populations, survivor leadership, as well as facilitating local education and awareness efforts. After multiple conversations with local organizations – the Utah Domestic Violence Coalition, the Utah Coalition Against Sexual Assault, Restoring Ancestral Winds, and DCFS, it was established that a state-wide needs assessment be conducted under the leadership of the Principal Investigator (Dr. Fukushima) and the Gender-Based Violence Consortium. A needs assessment is defined by Peterson and Alexander (2001) as “the role of needs assessment is to identify and also address needs.” It is a “tool for determining valid and useful problems.” Overall, a needs assessment is a “collection of data bearing on the need for services, products, or information.” The research team will conduct a mixed methods study to further understand the needs for service provision surrounding domestic violence, human trafficking and sexual assault. The Utah State-wide Needs Assessment employs mixed methods which triangulates qualitative and quantitative data collection. The methodology for this study involves survey distribution (N=293), followed by focus groups and/or interviews (N=41) with experts of domestic violence, sexual assault, and/or human trafficking. Data collection occurred between July and December 2021. Recruitment occurred after IRB approvals (IRB_00141188) online via social media and emails. Focus groups and emails were conducted remotely utilizing Zoom. Data collection occurred between July 2021 until May 2022.

Participants

293 individuals participated in the online survey and 41 individuals participated in focus groups and interviews. Participants were professionals with a wealth of experience working on domestic violence, sexual violence or human trafficking with an average year of experience for survey participants being 9.5 years and 11 years for interviewees and focus group participants. Expertise by types of violence varied with the highest of expertise in domestic violence (n=216), sexual violence (n=165), and child abuse (n=124). Of the 283 participants who disclosed their range of professional identities, the highest representation was with advocates (20%), mental health providers (18%), administrator/executive director/director (14%), and medical providers (8%), with participants identifying in smaller numbers as prevention and education (5%), victim service provider (5%), case manager/supervisor/manager (4%), housing provider (4%), receptionist/secretary (2%), researcher/analyst (2%), volunteer (2%), child welfare (1%), legal provider/lawyer (1%), outreach (1%), law enforcement (1%), social service provider (1%), and less than 1%: religious leaders and media/marketing. Survey participants were 89% female identifying with smaller participation from male and gender-nonconforming participants, 82% heterosexual with 19% identifying as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Asexual or Queer, with diverse racial participation with Asian and Hispanic / Latino slightly lower than the Utah population, and White over-represented, with other racial minorities in parity with Utah population. Survey Participants were able diverse with 17% identifying with living with a disability.Interviewees and focus group participants were predominantly women (95%), and heterosexual (80%), with smaller participation from men (5%) and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Queer (20%), and were closer to parity with Utah racial demographics, with larger participation form Alaskan Native/American Indian (5%). Participants were also geographically diverse. Although a large number were from Salt Lake County, participants also joined from southern, northern and eastern Utah. Additionally, 47% participants identified as survivors.

Community Perceptions

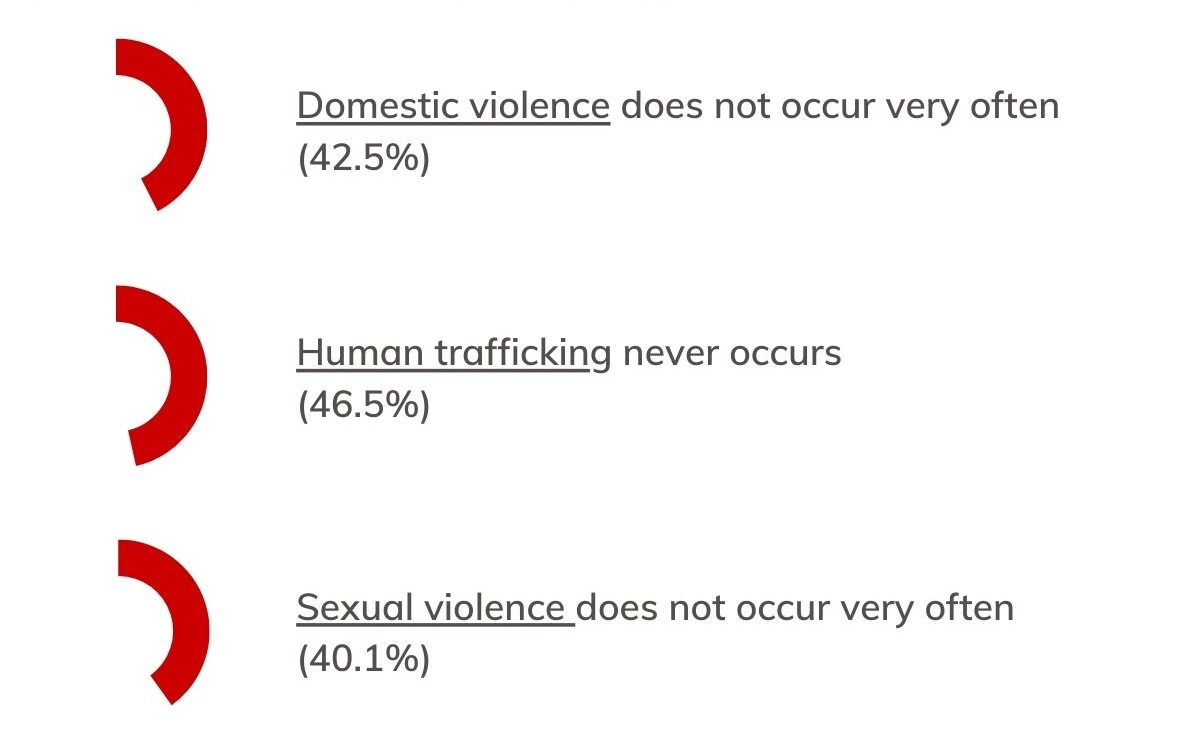

Misperceptions about domestic violence, sexual violence and human trafficking persist. Nearly 4 in 10 of the surveyed participants believe that the community believes that: domestic violence and sexual violence do not occur very often and that trafficking never occurs. Regardless of the perception that violence is not occurring very often or at all, there is a need to raise awareness about violence in Utah.

Marginalized Communities

In order to be effective at responding to violence, it is essential that governmental and nongovernmental responders address the response for the most marginalized in communities. There are a variety of marginalized communities, where this study brings to the fore specific communities and people:

- American Indian / Alaskan Native communities

- Communities of Color: Black, Latinx/a/o/Hispanic, Asian, and Pacific Islander

- Immigrant communities

- LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, Asexual) communities

- Communities living with a disability

American Indian / Alaskan Native

There are 8 federally recognized tribes in Utah: Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, Navajo Nation, Northwestern Band of Shoshone Nation, Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, San Juan Southern Paiute, Skull Valley Band of Goshute, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Ute Indian Tribe. Restoring Ancestral Winds is a tribal coalition that addresses stalking, domestic, sexual, dating, and family violence. RAW collaborates with UDVC and UCASA, Rape Recovery Center, as well as providers funded by DCFS work to support survivors of domestic violence, sexual violence, and human trafficking. Also, RAW has partnerships with the Strong Hearts Native Helpline and the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center. In 2021, Gentle Ironhaw Shelter opened in Blanding to house domestic violence survivors.

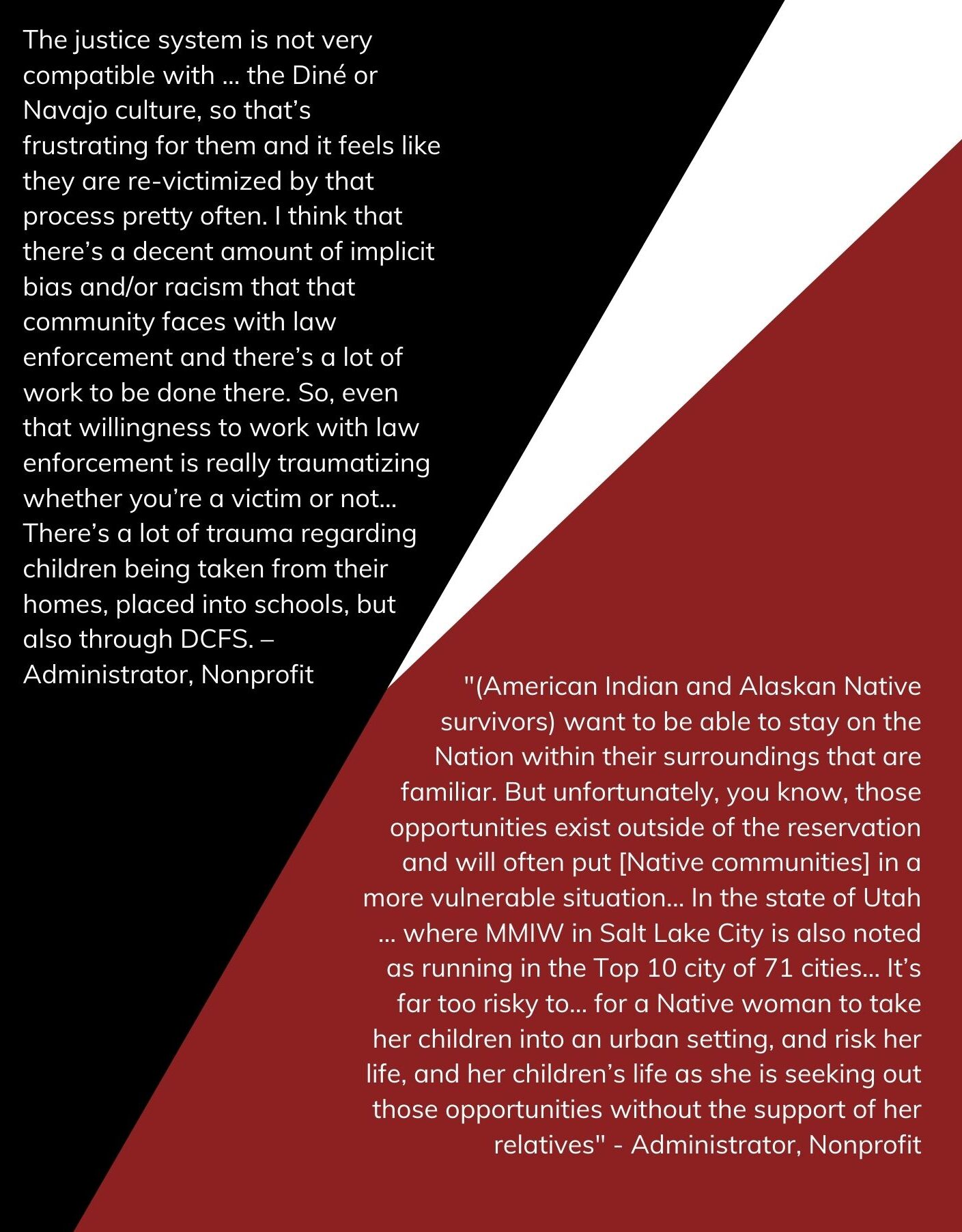

Domestic violence is deadly for Native people where four out of 5 Native women and girls are affected by violence with homicide rates 10 times the national average. And 1 in 3 Native women are raped in their lifetime. Utah is the 10th most dangerous place for Native peoples, with the highest numbers of missing and murdered indigenous women, girls and two-sprit cases (Lucchesi and Echo-Hawk 2018). Additionally, there is a need to address non-Native violence against Native people, where 80% of abusers are non-Native people.

There has been an increase in partnerships between Utah governmental representatives and Native leaders. In 2020, a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women task force was created, with representatives of Restoring Ancestral Winds. While there is a wealth of expertise, knowledge and desire to support Native communities, the AI/AN are truly under-resourced financially, where in the diverse tribes, there may be only one officer to investigate a region or one advocate to support survivors.

Although there are 574 federally recognized tribes, the diverse native communities continue to experience homogenization. Additionally, the rurality of tribal communities, means that survivors oftentimes traverse long-distances to have their needs met, distances that they do not have resources to travel or it may impact the ability for the survivor to engage with services if they are also parenting. For Native survivors accessing services, there is a need to increase education and awareness of serving diverse cultures. Participants described Native survivors experiencing re-traumatization when accessing resources with governmental and non-governmental agencies. Culture is incredibly important when responding to the needs of Native survivors. One interviewee described how justice responses to Native survivors might sometimes include advice, recommendations or processes that go against Native beliefs. There is a need to provide culturally aware services that work in collaboration with funding Tribal communities to provide the expertise and services. The Urban Indian Health Center was lauded as a model. Many Native leaders would like to support non-Native organizations, however, they are under-resourced in people and time to lend their expertise to other organizations. Therefore, there needs to be two-fold forms of resourcing occurring for Native communities: 1) increasing funds to Native organizations and 2) diversifying recruitment in organizations to actively recruit Native experts. Additionally, federal funds have been utilized to support traditional ceremonial forms of healing as a means to foster culturally aware responses to violence – this is highly recommended that such resourcing is supported.

Recognizing that there are different mechanisms of reporting of violence, this impacts what is known about Native communities. Some tribal communities report to SANE nurses, where information and reporting is centralized with Public Health Services. Or others are working with American Indian Health Services. Some data surrounding violence against American Indians and Alaskan Natives focuses on domestic violence, excluding sexual violence. Additionally, Indian nation is fluid and broad, which means that Native communities may be accessing non-native services.

Communities of Color

Black, Latinx/a/o/Hispanic, Asian, and Pacific Islander

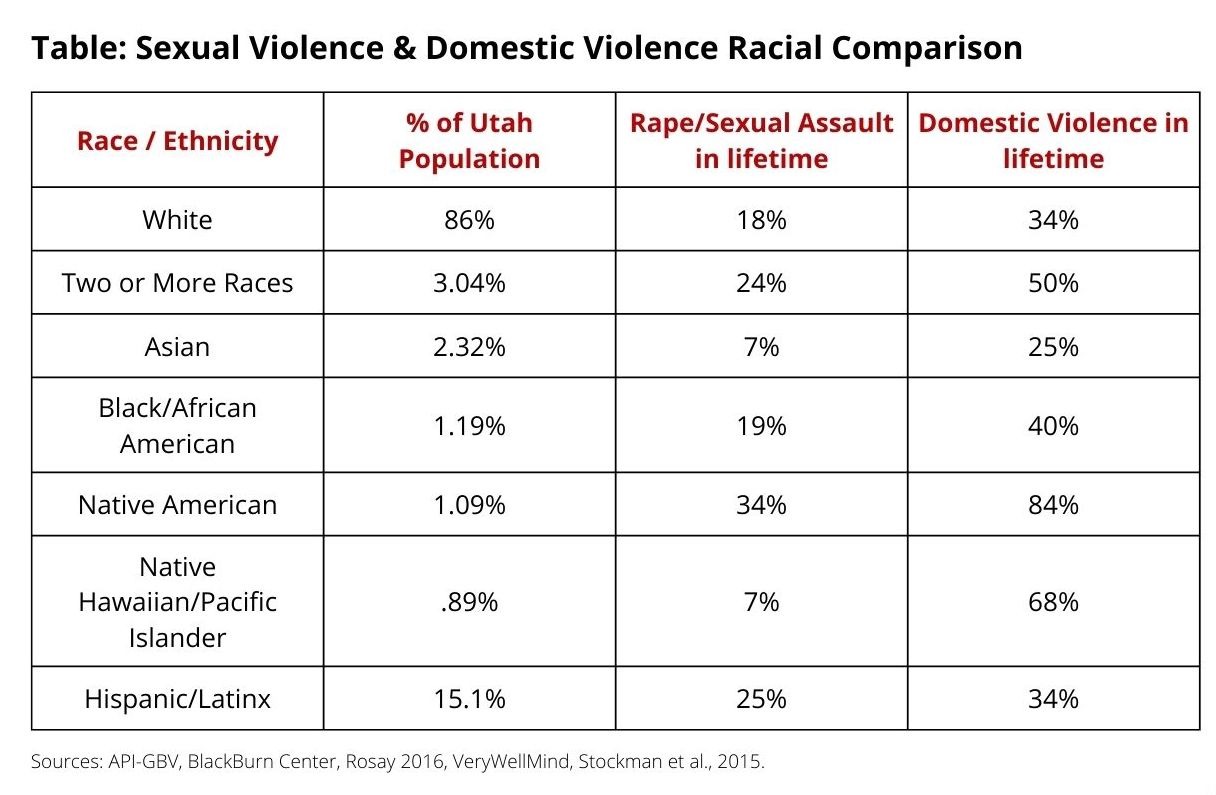

Utah is increasing in diversity with a population increase between 2010 and 2020 of 17.4% (Clair 2020). Although Utah is growing in diversity, an ongoing concern is how to support the racially and ethnically diverse communities that experience domestic violence, sexual violence and human trafficking. Although organizations such as Comunidades Unidas, Pik2AR, Utah Coalition Against Sexual Assault Spanish language-line, Asian Association of Utah, and coalition members support survivors regardless of race, there is a need to address race and ethnicity in Utah. Color-blind racism is the norm in Utah, where people do not “see race.” However, “We cannot un-will ourselves to un-see something that we’ve already seen.” Race is a powerful social identity, where diverse and culturally aware responses to violence are much needed in the state. Survivors are hesitant to access services due to the perception of resources being for “whites” or unable to accommodate diverse communities. Additionally, there is a need to provide specialized services and groups for diverse communities to grapple with how there are layers of oppression that they experience due to violence, when seeking out services/resources, and when attempting to leave or heal from violence or abuse. As data shows, communities of color are being impacted by domestic violence and sexual violence at a greater rate than their white counterparts. Communities of color are a central factor that impacts who is more likely to experience being trafficking where communities of color are disproportionately represented in sexual economies, and in effect vulnerable to trafficking (Butler 2015; Fukushima 2019). This does not make communities of color more violent, but rather, highlights the ongoing impacts of structural violence and decades-old discriminatory policies, like redlining, on communities of color that also exacerbate conditions of abuse.

Immigrant Communities

Utah refers to itself as a “welcoming,” conveying that there are efforts in support New Americans who welcome. 9% of the Utah population is immigrant (American Immigration Council 2020). Immigrant communities include US diasporas who are also indigenous (for example, Native people whose peoples are not traced to the Utah region), refugees, asylum seekers and migrant laborers. The top national origins in Utah are Mexican, Indian, Venezuelan, Peruvian, and Canadian. 140,517 people in Utah lived with at least one undocumented family member. And 1 in 9 Utah workers are immigrant. Immigrants are found laboring in a range of industries, with higher representation in building and grounds maintenance, construction/extraction, farming/fishing/forestry, production, and food preparation and serving. These industries are also the same industries where trafficking is more likely to occur. The Violence Against Women Act and Trafficking Victims Protection Act include protections for immigrant survivors of violence, where they are able to access services and immigration relief. However, despite the resources available to immigrant communities, they continue to face a range of barriers including: staying in abusive conditions due to fear of law enforcement, lack of multi-lingual services, and an absence of culturally responsive resources to new comers who experience violence. Although UCASA and COLAVI (Colavi: La Coalición Latina En Contra De La Violencia Intrafamiliar) provide support in Spanish, Spanish is just one of the many languages preferred by people from Latin America, and even a second language for people whose preferred language are Zapotec, Mixteco, Quechua, Guarani, among the many languages spoken in Latin America, which it is estimated that 560 indigenous languages are spoken in Latin America (Existe Ayuda, n.d.). Language access and immigration relief are central to supporting immigrant survivors of violence.

Over 1 in 2 of the surveyed believe survivors fear calling the crisis-line due to their legal status and over a third found crisis-line insufficient due to there being no interpreter/translation provided. Fear due to their legal status is also a barrier for immigrant survivors accessing housing, when seeking legal services, and when reporting crimes to law enforcement. Nearly half of the participants also believe that survivors do not seek out medical services due to fear about their legal status. And 1 in 2 believe that survivors are unable to have their immigration needs

LGBTQIA+

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, Queer survivors of violence experience a range of violence that are higher rates than their heterosexual counterparts. While it is estimated that 35% heterosexual women will experience, rape, physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime, for gay men it is 26%, for lesbian it is 44%, and 61% for bisexual women (NISVS 2010). And while it is estimated that 1 in 5 women and experience sexual violence in a lifetime (CDC 2021), the rates for transgender people is nearly 1 in 2 (HRC Foundation 2021).

Similar to communities of color, LGBTIQ survivors of violence continue to feel that there are not enough safe spaces for them. And that overall, LGBTIQ+ community members continue to have lower rates of help-seeking due to a range of concerns with being “outed” or experiencing discrimination (NCAVP 2016; Barker 2022). Particular areas of need and barriers for LGBTIQ+ is with accessing housing and healthcare (Belknap et al., 2009).

Disability

6.8% of Utahn’s live with a disability, and 11% of those living with a disability are uninsured. There are a range of challenges that are faced in addition to experiencing violence. Participants described how it was difficult to put people into boxes that are required for disability services. It is common for domestic abusers to threaten the safety of animals to compel survivors to stay in abusive conditions. Although HB175 expands protective order protections for animals, there exist a range of disabilities that impact survivors of violence beyond emotional animal assisted services. People living with a disability have a higher prevalence of abuse, and are three times more likely to be sexually assaulted compared to peers without a disability (NCADV 2018b) with other studies conveying that people living with a disability are 7 times more likely to experience sexual assault (Shapiro 2018). And 40% greater chance of experiencing intimate partner violence. A review of 54 cases in Florida found that 28% of human trafficking involved individuals with intellectual disabilities (Nichols and Heil 2022).

Services & Response

Change

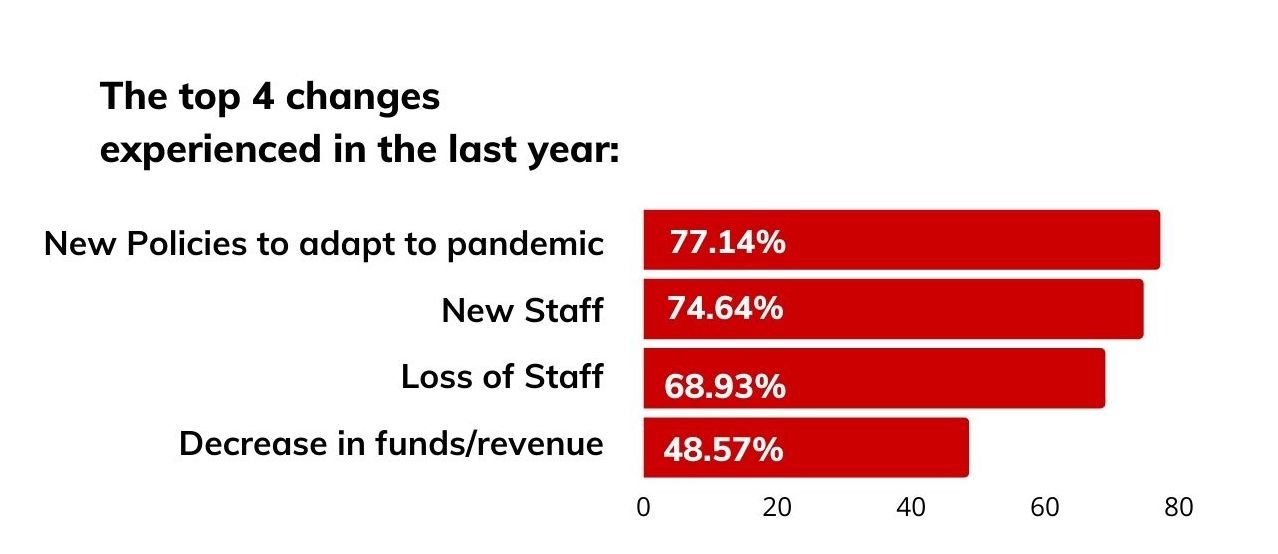

There are 21 organizations that provide services to survivors of sexual violence and 26 organizations to survivors of domestic violence. Oftentimes these organizations are providing services for multiple types of abuse. And human trafficking responses is coordinated through the Utah Trafficking in Persons Task Force. During the past year, 83% of the participants described how their organizations experienced change, with the most change with regards to adapting to the global pandemic, new staff, loss of staff, and decrease in funds/revenue.

In the past 5 years there were a range of positive changes including how the #MeToo movement led to more visibility surrounding sexual violence, there seems to be a shift away from silence in Utah, collaborations are growing, and pandemic created more flexibility to support survivors of violence and responders.

Although there were positive changes, negative changes included increase in complexity of cases, increase in fear of lethality, technological/digital divide, and the response unable to keep up with the growing numbers of survivors.

Barriers

Survivors in Utah face a range of barriers, that impact their ability to access services. In particular, they fear their abuser, do not want their abuser to get into “trouble”, lack knowledge about resources, lack financial resources to leave, or are unable to leave due to child care for children.

Survivors in Utah face a range of barriers, that impact their ability to access services. In particular, they fear their abuser, do not want their abuser to get into “trouble”, lack knowledge about resources, lack financial resources to leave, or are unable to leave due to child care for children.

There are not enough resources to survivors. Over 4 in 10 of respondents do not believe there are enough to support survivors of domestic violence. Over half of respondents do not believe there are enough resources to support survivors human trafficking. And nearly 4 in 10 of respondents do not believe there are enough resources to support survivors of sexual violence.

Despite the wealth of knowledge and years of expertise, 1 in 2 of respondents thought about leaving their organizations because of feeling overwhelmed or overworked, desires to earn more money or receive better benefits, lack of support from leadership, the organization’s culture, or trauma from their work.

Nearly 1 in 2 of the participants have thought about leaving their organizations.

Needs

The top five needs for survivors of domestic violence, sexual violence and human trafficking: housing, financial support, emotional support, mental health, and family support.

5 Top needs for survivors of violence:

- Housing

- Financial support

- Emotional support

- Mental health

- Family support

Crisis-line

Survivors of sexual violence, domestic violence and human trafficking need to know where to call to reach out for help. The top reasons why survivors call a crisis-line is because they are seeking safety, they need emotional support, or assistance with urgent needs such as housing, medical, and other needs. Current challenges faced by crisis-line services are that survivors are unaware of the crisis-line, survivors fear calling due to their legal status, the crisis-line needs more staff support, survivors are denied services/support due to eligibility requirements, or there was no interpreter/translation provided.

Housing

A majority of the participants believe that housing for survivors of sexual violence, domestic violence and human trafficking are insufficient. And 4 in 10 believe that housing is inaccessible. The top five barriers survivors face when accessing housing is that there are either not enough beds or housing options. Housing options are unaffordable to survivors. In the past year, housing in Utah increased by 3.8%. For survivors of violence the inability to afford housing may impact their ability to leave abusive conditions or heal from the violence they experienced. The limited options for housing in Utah and restrictions with funding also means that survivors may be considered ineligible for housing. Survivors may also be unaware of housing services. And for immigrant survivors, although Utah is welcoming to migrant community, those whose traffickers or abusers used their legal status to compel them to stay in abusive conditions means that survivors are also afraid of authorities due to their legal status.

Utah's strong owner rights have led victims who are renters and call law enforcement for safety, to experience consequences - landlord evictions for "disturbing the peace." In addition to being uprooted from their homes, survivors who are forced to evict under these circumstances face a range of additional barriers of not receiving their deposit back for breaking the lease (Peterson et al., 2021).

Transportation

Transportation came up regularly during the interviews and focus groups. Participants described how lack of transportation or the inability to travel long distances to services, impacts survivors. Although there are resources in all parts of Utah, for survivors in rural settings finding their way to services is not always easy, and may add further stress.

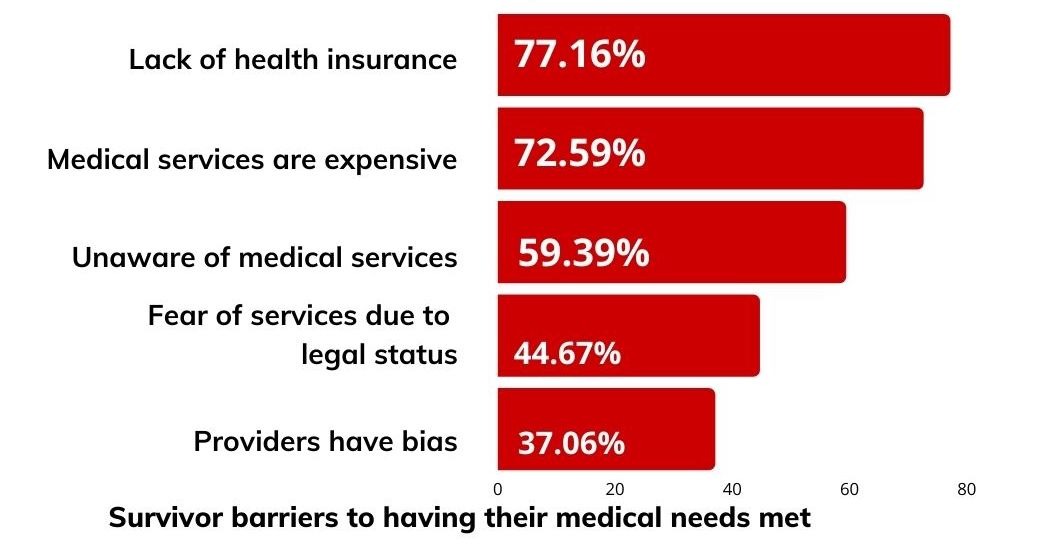

Medical

Medical services are essential and a basic need from physical to mental health needs. Survivors of IPV accrue higher costs compared to non-survivors due to immediate aftermath of violence as well as long-term issues (Mclean and Bocinski 2017). The lifetime costs for survivors of rape is estimated $122,461 per victim (Peterson et al., 2017). Trafficking survivors are accessing healthcare while being trafficked, with 68.3% being seen at the emergency room (Lederer and Wetzel 2014). In the aggregate, respondents of this study top five reasons survivors of violence sought out medical services due to needing urgent care, substance use treatment, primary care, care for another family member, or to receive reproductive services. While there are many medical needs, survivors continue to face barriers due to their lack of health insurance, the costs associated with medical care, they are unaware of medical services, fear service providers due to their legal status, and experience bias or discrimination from medical providers.

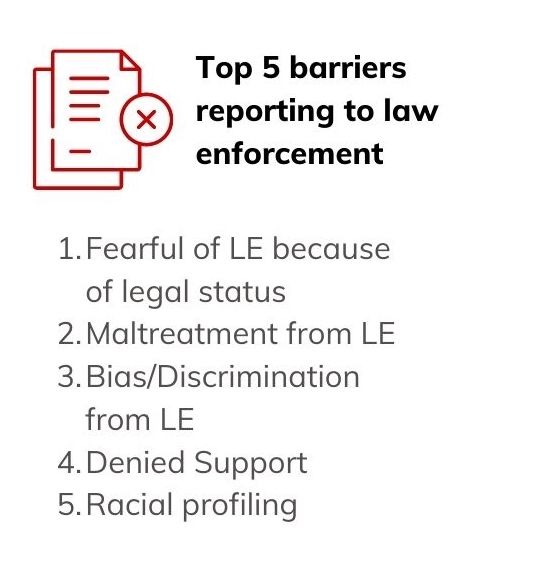

Justice & Law

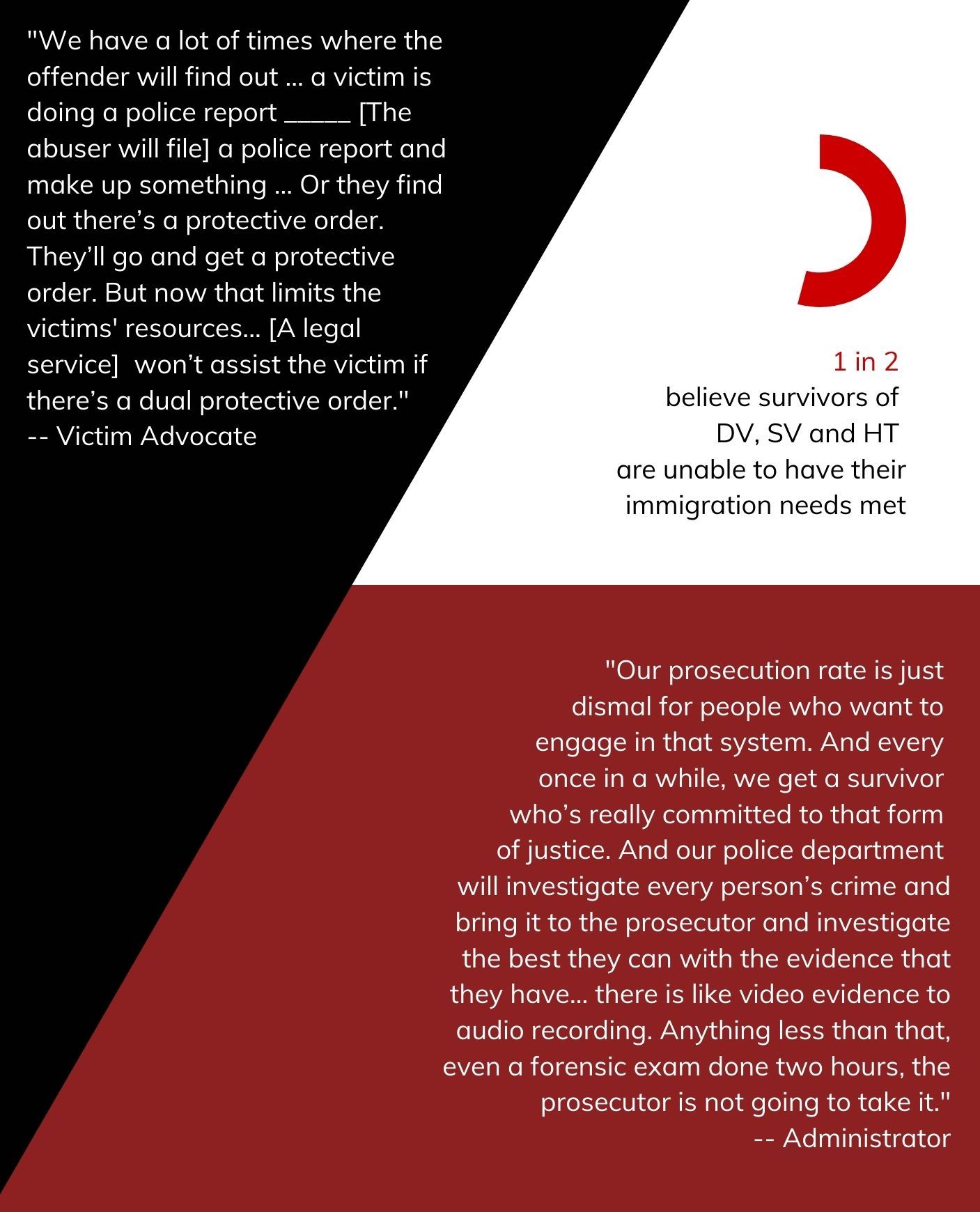

Domestic violence is a misdemeanor and law enforcement are required by law to use reasonable means to protect victims and prevent further violence (Utah Code sections 77–36–2.1 & 2.2). The top five reasons that survivors reach out to law enforcement are for safety/protection, filing a complaint, aiding in an investigation, criminal system related issues, or probation. For sexual violence survivors, only 1 in 10 of sexual assault cases end in a conviction with people of color three times as likely to be charged in contrast to a white perpetrator (Jacobs 2021). Survivors face a range of barriers when reporting to law enforcement including being fearful of law enforcement due to their legal status, experiencing maltreatment from law enforcement, bias and discrimination from law enforcement, being denied support, and racial profiling.

In addition to enforcement, survivors of violence have a range of legal needs. This includes protective orders, restraining orders, custody of a child, divorce, legal needs related to domestic violence and prosecution of their abuser. After reporting to law enforcement, legal needs continue to be unfulfilled because they are expensive, survivors are unaware of services, there is a need for more providers/staff, fear of services due to their legal status, and survivors were denied support/services. Filing protective orders can be a lengthy process for survivors. And abusers violate protective orders (Gillis 2021), and take advantage of the system by finding ways to block survivors from receiving protection or representation. 1 in 2 of the participants believe that survivors are unable to have their immigration needs met. Overall, survivors of violence have varying perceptions of justice – for many of the interviewees participants described the need for more education as justice and transformative forms of justice that do not rely on the criminal legal system that is intended to be healing for all with accountability (Mingus 2022). A transformative justice question is by focusing response on: what do survivors and people who have caused harm need?

Campus Response

Universities and educational environments are an important site of prevention. However, current challenges have emerged on campuses despite Title IX resources and processes. These challenges have included:

- Inability to support students after the student transfers from another institution

- Difficulty of victim confidentiality; conflicts with mandated reporting

- Polyvictimization (i.e., stalking, domestic violence, sexual assault intersecting)

- Difficulties reporting

- Desire for institutional accountability

- International students are not entitled to the same support/benefits

Although it appears that some institutions are on the decline with rape or fondling reporting, it is unclear if rape and other forms of assault are on the decline or if victims are not reporting. Additionally number of incidents is not indicative of campus severity - it only illuminates that reporting is occurring.

Campus programming in university settings during domestic violence awareness month (October) and sexual violence awareness month (April) has increased discussions about violence and in effect, campus reporting.

Violence Prevention

Violence prevention in the state of Utah encompasses a state-wide conference on domestic violence (organized by the Utah Domestic Violence Coalition in September or October (in collaboration with Utah Association of Domestic Violence Treatment), annual state-wide conference on sexual violence during the month of March (organized by UCASA), and an annual symposium on human trafficking organized by the University of Utah and the Utah Trafficking in Persons Task Force (in January). During the month of October DVAM (Domestic Violence Awareness Month) activities are ongoing throughout the month. Additionally, Sexual Assault Awareness Month has led to a robust amount of activities including most recently Denim Day at the Capitol Hill on April 27, 2022. And in 2021, Stop the Violence Utah was created to foster a state-wide campaign (https://stoptheviolenceutah.org/). State-wide coalitions, local nonprofits, academic institutions, continue to invest time and energy into organizing educational content on domestic violence, sexual violence and human trafficking. However, these endeavors are under resourced and education in primary education limited. Primary education on domestic violence continues to put onerous on victims to affirmatively refuse, instead of teaching consent (Villarreal and Evelyn 2021). The primary need to foster more education and prevention is to fund these endeavors, support education and prevention in rural settings, provide more resources to organizations to staff prevention and education, foster relationships between community and organizations, and continue to make opportunities visible.

The priority areas for violence prevention in the state of Utah, based on needs:

- Increase funding to prevention efforts

- Increase awareness in rural communities

- Increase campaigns targeted at increasing survivor awareness

- Increase ins staff/providers dedicated to prevention and education efforts

- Build community partnerships to foster trust between organizations and the community's served.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: increase monetary resources to respond to marginalized communities

Alaskan Native/American Indian, People of Color, LGBTQIA, immigrant, and people living with disabilities continue to experience being under-deserved. In order to support dynamic communities, have complex cultural, social, and linguistic needs, organizations need more resources to house, provide programming, offer culturally relevant services, and hire multilingual staff.

Recommendation 2: Systematic data collection & centralized information sharing

Currently there is no centralized mechanism for data collection to track survivor needs overtime. Additionally, while there are coalitions that collect some information and reporting is required for DCFS funded entities, the public sharing of data to inform communities on progress and resourcing survivors is much needed. Resourcing the coalitions to hire staff to manage data and to share across coalitions in de-identified way will help not only support survivors, but also assist the various collectives in moving forward with a response that is data driven.

Recommendation 3: Culturally aware responses and trauma-informed response

There is a need to foster culturally aware and trauma-informed services and response. There are multiple promising models that it would benefit the state to invest in to respond to domestic violence, sexual violence and human trafficking. These models include: trauma-informed systems, housing first, human rights, theory driven responses (i.e., feminist multicultural / critical race theory / indigenous epistemologies), and community coalition and partnerships. What came through in the interviews and surveys is the need for translation and the strength of culturally responsive services.

Acknowledgements

The research team is incredibly thankful for the resources and support provided by the Utah Domestic Violence Coalition. In addition to a partnership with UDVC, the research team worked to promote the study through the informal support of the Restoring Ancestral Winds, Utah Coalition Against Sexual Assault, and the Department of Family and Children Services. The report is authored by the Principal Investigator, but is in gratitude to the undergraduate researchers that supported the study by recruiting participants and assisting with the qualitative data. In particular much appreciation to Mikaila Barker, who was so instrumental to the project in the IRB application, recruitment and analysis. Additional appreciation to undergraduate researchers: Tony (Liu) Chen, and Mariah Montoya. And much gratitude to Sohyun Park who served as the graphic designer and media researcher for the project and the Gender-Based Violence Consortium. The students who worked on this project were supported by the Office of Undergraduate Research, Honors College, and the Francis Family Fund. Additionally, this report is made possible due to the survivors and experts in social services, advocacy, community-based organizations, health care, academia, law enforcement, governmental organizations, among many other professions whose everyday calling and commitment are to respond to the needs of survivors of domestic violence, sexual violence and human trafficking.